Most wives don't want to be breadwinners

This is part 1 of a 2-part post on working mothers. Recent poll sheds light on the debate over balancing career and family

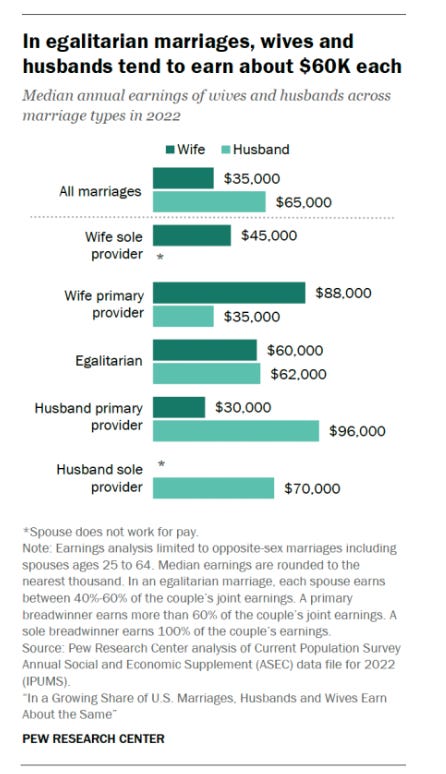

Never before have women’s choices seemed more numerous on the macro scale than they do today. A Pew Research study from 2023 shows that couples with a breadwinner wife have more than tripled since the 1970s, up to 16% now, and the same is true for “egalitarian” households in which both spouses earn roughly equal amounts (29% of today’s intact families). The remaining 55% of households have a husband breadwinner.

Advocates for increased female presence in the workforce will view these stats as evidence of a trend in the right direction. Yet, what these numbers also miss is perhaps the most important question of all: What do these women actually want their financial arrangement to be, and how does that impact their marriages?

What do wives actually want?

My husband is currently a resident doctor training to become a surgeon. Perhaps in no profession are more highly qualified and educated individuals worked harder, for less money, and for more years than medical residents. He often works 90-hour weeks and makes less per hour than I did as a part-time nanny during graduate school. While, in my weaker moments, I sometimes wish for even a temporary release as the primary parent to our young children, I would never want to adopt the responsibility that comes with my husband’s “freedom” to commit so much of himself to work.

My husband faces the same dilemma that virtually every father does. He is the parent and spouse responsible for ensuring we have enough money to keep our house, feed our kids, pay medical bills, and fix stuff when it breaks. Similar to the immense pressure a mother feels to provide the optimal care and environment for her kids, balancing education with play, love with discipline, and support with independence, a father feels the pressure of providing genuine financial stability that allows his wife to create that optimal home.

The primary parent’s responsibilities largely depend on the ability of the primary breadwinner to meet the family’s basic material needs. After all, it’s difficult to provide a healthy home for your kids while facing threats of eviction or the hounding of debt collectors.

Through my personal and professional experiences, I’ve found that what most wives, and particularly mothers, want is the freedom to work that their husbands seem to have without the responsibility to earn that their husbands certainly have.

In other words, most wives don’t want to be breadwinners because the role of breadwinner is defined not by the freedom to work, but by the responsibility to provide for the family’s financial needs.

We often see the greater number of hours men spend at work as a greater freedom to pursue the meaning we would like to get from work. Yet, nearly 40% of fathers wish they could work less and spend more time with their kids. So, is it fair (or even helpful) to separate the freedom from the responsibility, or to assume that the spouse who works more automatically feels more fulfilled?

In fact, the same dilemma happens in reverse. Many full-time working parents may occasionally long for what their spouses have - the freedom to work less and spend more time with their kids - without acknowledging the responsibilities that lifestyle entails.

What about wives who have to work?

Of course, for a percentage of households, wives work as a means to financial stability, not necessarily self-actualization or enjoyment. For example, that same Pew study showed that 6% of married couples have a wife-as-sole-provider. However, these couples tend to report lower well-being than other couples, according to a 2024 study.

This decreased well-being is likely related, at least in part, to significantly lower household income. The median household income for these wife-as-sole-provider marriages is by far the lowest of any family type, at $45,000 annually. By comparison, the median income for husband-as-sole-provider is $70,000 annually (in many places, an actual livable wage). For marriages in which both spouses contribute financially, the total annual household income shoots up to roughly $120,000.

Given such a discrepancy in these wife-as-sole-provider households, could we go so far as to say that the tripling of this financial arrangement from the ‘70s to now is less a sign of empowering progress and more a sign of increased economic insecurity for more couples, stemming from husbands facing unemployment they didn’t choose?

Perhaps most of these couples would prefer a different financial arrangement if they could have it?

Responsibility gives birth to meaning

There’s nothing wrong with preferring to work for meaning rather than strictly to make ends meet. In fact, in a perfect world, everything we do would bring an infinite sense of meaning to our lives. I wouldn’t be a therapist if I didn’t find it highly meaningful.

A problem only arises for couples when we undersell the meaning of a wife’s role at home or the responsibility of a husband’s role at work.

When this happens, both spouses find themselves in a grass-is-always-greener situation, wishing for the impossible: a sense of sustained meaning without the associated responsibility.

By treating parenting as if it’s all responsibility and no meaning, we rob mothers of the pride they should be allowed to take in creating the future. Without the next generation, there is no future. And without a future, what joy can we really expect to glean from life?

On the other hand, by treating work as if it’s all meaning and no responsibility, we place career on a pedestal that leaves the parenting spouse feeling resentful and the breadwinner spouse feeling misunderstood and underappreciated.

The antidote

Nothing meaningful in life comes without the strings of responsibility inseparably attached. As my physics teacher used to say, “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” He was talking about the transfer of energy, but the saying is just as true in family life. If the problem is simplistic comparison, my proposed solution is simple: gratitude and negotiation.

The nagging envy I felt over my husband’s freedom to work outside of the home all but vanished the moment I realized I would never want the responsibility attached to that freedom. I’d much prefer the responsibility of primary parent than primary earner, and I’m thankful we’re blessed enough to have made that arrangement work for us so far.

I will admit, though, that I’m not an advocate for the strategy of indefinite grinning and bearing it. As much as marriage calls for lifelong gratitude, it also calls for lifelong negotiation.

If, after much honest thought, prayer, and discussion, a couple finds that their career/family arrangement isn’t working, can a different (hopefully better) arrangement be negotiated?

Certainly, some seasons will be more flexible than others. For example, medical residents get virtually zero control over their schedules. Little negotiating about my husband’s work schedule happens for us in our current season of life. But, that won’t always be the case. One day his schedule will be far more flexible and mine will likely be less flexible than it is now. When that day comes, we’ll negotiate a different career/family arrangement than we have now. Not to mention, as kids age, they need their parents for fewer hours of the day, a reason for mothers with young kids to feel hopeful that, even if they can’t fully answer their call to a career right now, one day they will be able to.

By making gratitude a habit, we’re better equipped to have effective negotiations in those more flexible seasons while being far better prepared to grin and bear it, together, through the inflexible ones.